When the body’s sodium levels dip below normal, the ripple effect can be serious. This article breaks down everything you need to know about Hyponatremia-from the warning signs that show up in everyday life to the medical steps that bring levels back to safety.

Quick Take

- Hyponatremia is defined as serum sodium< 135mmol/L.

- Common symptoms include nausea, headache, confusion, and in severe cases, seizures.

- Root causes fall into three groups: excess water, sodium loss, or a mix of both.

- Treatment ranges from fluid restriction to hypertonic saline, depending on severity.

- Prompt medical attention is crucial-delay can lead to permanent brain injury.

What Is Hyponatremia?

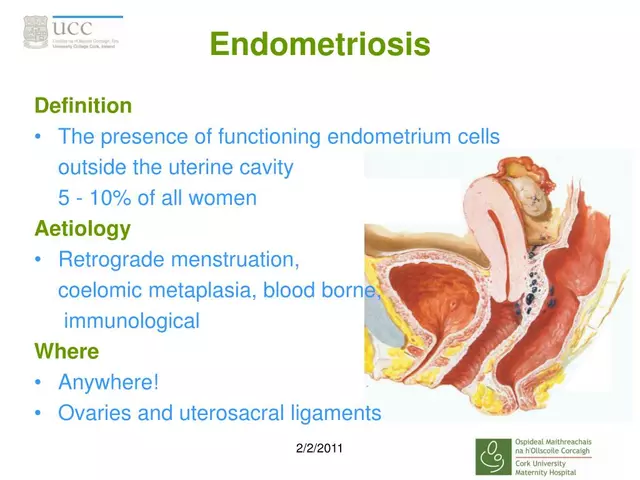

Hyponatremia is a medical condition where the concentration of sodium in the blood falls below the normal range, typically under 135mmol/L. Sodium helps regulate fluid balance, nerve transmission, and muscle function. When its level drops, water moves into cells, causing them to swell-particularly dangerous in brain cells because the skull limits expansion.

Why Sodium Matters

In the body, Sodium is the primary extracellular cation. It works hand‑in‑hand with potassium to maintain the osmotic gradient that drives water across cell membranes. The kidneys constantly fine‑tune sodium excretion based on intake, hormonal cues, and blood pressure.

Key Hormone: Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH)

The hormone most often blamed for low sodium is Antidiuretic Hormone (also called vasopressin). ADH tells the kidneys to re‑absorb water, concentrating urine. When ADH is released inappropriately, the body retains water faster than sodium can be excreted, diluting blood sodium.

Who Is at Risk?

Anyone can develop hyponatremia, but certain groups face higher odds:

- Elderly patients-kidney function declines with age.

- Athletes who over‑hydrate during endurance events.

- People on diuretic therapy for hypertension or heart failure.

- Patients with lung diseases, like pneumonia or COPD, that trigger ADH release.

- Individuals with psychiatric conditions who binge‑drink water (psychogenic polydipsia).

Symptoms: From Mild to Life‑Threatening

The brain’s sensitivity to swelling makes neurological signs the most telling. Early, mild symptoms often mimic a stomach bug or flu:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Headache

- Fatigue or lethargy

As sodium drops further, mental status changes appear:

- Confusion or disorientation

- Muscle cramps or weakness

- Seizures

- Decreased consciousness, potentially leading to coma

Any sudden change in mental clarity warrants urgent testing.

Root Causes: The Three‑Way Split

Clinicians classify hyponatremia by the underlying mechanism:

- Excess water intake that overwhelms renal excretion.

- Sodium loss through kidneys, gut, or skin.

- Combined loss and dilution-the most common clinical scenario.

Below is a concise table of the most frequent causes, their physiological pathway, and typical serum sodium ranges seen in practice.

| Cause | Mechanism | Usual Serum Sodium |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive water drinking (psychogenic polydipsia) | Water overload dilutes sodium | 120-130mmol/L |

| SIADH (Syndrome of Inappropriate ADH Secretion) | Inappropriate ADH release → water re‑absorption | 115-125mmol/L |

| Thiazide or loop Diuretic therapy | Renal sodium loss | 120-130mmol/L |

| Heart failure (fluid overload) | Reduced effective circulating volume → ADH rise | 115-125mmol/L |

| Adrenal insufficiency | Aldosterone deficiency adds sodium loss | 110-120mmol/L |

Diagnosis: How Doctors Confirm Low Sodium

A simple blood draw measuring serum sodium is the first step. However, clinicians also assess:

- Serum osmolality - to differentiate true hyponatremia from hyperglycemia‑induced dilution.

- Urine sodium and osmolality - high urine sodium suggests renal loss or SIADH, while low urine sodium points to extrarenal losses.

- Volume status (clinical exam) - hypovolemic, euvolemic, or hypervolemic categories guide treatment.

Imaging, such as a head CT, is reserved for severe neurological symptoms to rule out intracranial bleed.

Treatment Options: Matching Therapy to Severity

Therapeutic decisions hinge on three factors: how low the sodium is, how fast it fell, and the patient’s volume status.

1. Fluid Restriction

For mild, euvolemic cases-especially SIADH-doctors often start with a Fluid Restriction of 800-1200mL per day. The goal is to let excess water be excreted naturally.

2. Hypertonic Saline

Severe symptoms (seizures, coma) demand rapid sodium correction. Hypertonic Saline (3% NaCl) is infused in controlled boluses (typically 100mL over 10minutes) to raise sodium by 4-6mmol/L in the first hour. Ongoing monitoring avoids over‑correction, which can cause osmotic demyelination.

3. Vasopressin Receptor Antagonists

When ADH is the culprit, drugs like tolvaptan-a Vasopressin Receptor Antagonist-promote free water excretion without sodium loss. They’re used in euvolemic or hypervolemic hyponatremia when fluid restriction fails.

4. Salt Tablets or Oral Saline

Mild cases in out‑patients may be managed with oral salt tablets (1-2g) or isotonic saline (0.9% NaCl) to gently raise sodium levels while monitoring for fluid overload.

5. Address Underlying Causes

Stopping offending diuretics, treating heart failure, correcting adrenal insufficiency, or managing lung disease are essential for durable results.

Managing Hyponatremia at Home

After discharge, patients should:

- Follow any fluid‑intake limit precisely-use a measured pitcher.

- Weigh themselves daily; a sudden gain >2kg suggests fluid overload.

- Stay attentive to recurrent headaches, nausea, or mental fog.

- Keep a medication list handy; if a new diuretic is added, contact a clinician quickly.

Regular blood tests (once a week initially) let doctors track sodium trends.

When to Seek Emergency Care

If you experience any of the following, call emergency services immediately:

- Severe confusion, inability to stay awake, or seizures.

- Rapidly worsening headache or vomiting.

- Sudden weakness that impairs walking.

Time is brain-early correction prevents permanent damage.

Prevention Tips

Simple lifestyle tweaks can keep sodium in check:

- Avoid drinking large volumes of water during endurance sports; use sports drinks with electrolytes instead.

- Discuss any new diuretic or blood‑pressure medication with your doctor, especially if you have heart or kidney disease.

- Stay hydrated but follow thirst cues-not a preset schedule.

- For chronic illnesses, have periodic labs (electrolytes, cortisol) as part of routine care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a low‑salt diet cause hyponatremia?

A modest reduction in dietary salt rarely leads to hyponatremia on its own. The condition usually requires excess water intake or a medical factor that forces the kidneys to lose sodium.

Why do athletes sometimes develop hyponatremia?

Endurance runners or cyclists can over‑hydrate, especially when they rely on plain water. Sweating also loses sodium, so the combination dilutes blood sodium enough to cause symptoms.

Is it safe to correct hyponatremia quickly?

Rapid correction is reserved only for severe neuro‑symptoms and must be tightly monitored. Raising serum sodium more than 8‑10mmol/L in 24hours can cause osmotic demyelination, a serious brain injury.

Can hyponatremia recur after treatment?

Yes, if the underlying trigger isn’t addressed. Ongoing fluid restriction, medication review, and management of chronic illnesses are key to preventing relapse.

What lab values confirm hyponatremia?

A serum sodium level below 135mmol/L, coupled with low serum osmolality (<275mOsm/kg), confirms true hyponatremia. Urine tests help differentiate the cause.

Understanding the signs, causes, and treatment paths equips you to act fast and stay safe. If you suspect low sodium, don’t wait-talk to a health professional and get the right labs done.

Matthew Moss

It is imperative for every citizen to be aware of the dangers posed by low sodium levels. The nation’s health depends on informed individuals who monitor their intake. Hyponatremia can undermine productivity and national strength. Vigilance and prompt medical attention are duties we owe to our country.

Antonio Estrada

Understanding the balance of electrolytes invites a deeper reflection on bodily harmony. When sodium drops, the brain’s function can be subtly altered, affecting cognition. Therefore, regular testing becomes an act of philosophical self‑care. It is wise to keep a log of symptoms and discuss them with a healthcare professional.

Sumeet Kumar

Staying hydrated is great, but remember that water alone isn’t always the answer 😊

Endurance athletes especially should mix in electrolytes to keep sodium from slipping too low.

Listening to your body’s thirst cues can save you a lot of trouble.

Maribeth Cory

When you notice recurring headaches or a fuzzy mind, it’s a sign to check sodium.

Don’t wait for severe symptoms; early labs can prevent complications.

We’re all in this together, so share your experiences with others.

andrea mascarenas

Check your meds and stay on top of labs.

Stephanie Watkins

It’s a good practice to keep a medication list handy.

If a new diuretic is added, notify your doctor right away.

That way you can adjust fluid intake before hyponatremia develops.

Zachary Endres

Whoa, the brain really feels the impact when sodium drops!

One minute you’re fine, the next you’re confused.

That’s why emergency care is crucial for severe cases.

Don’t underestimate those subtle warnings.

Ashley Stauber

Honestly, the hype around over‑hydration is overblown.

Most people can handle plain water without crashing.

Only a tiny fraction develop true hyponatremia.

So let’s not scare everyone away from drinking.

Amy Elder

Keep an eye on your sodium but don’t freak out.

Balance is key.

Erin Devlin

Great info!

kristine ayroso

i think the article missed the point that many ppl dont even know what hyponatremia is.

also the tips about sports drinks are kinda basic.

maybe add some real world case studies?

Jennifer Banash

While the content is generally accurate, there are a few grammatical inconsistencies that deserve attention.

For instance, the phrase “serum sodium2kg suggests fluid overload” appears to contain a typographical error.

Clarifying that would improve credibility.

Overall, the article is informative.

Stephen Gachie

Hyponatremia, though often overlooked, warrants careful consideration within the broader context of electrolyte homeostasis.

First, the kidneys serve as the principal regulators of sodium balance, employing intricate mechanisms that respond to both hormonal signals and intravascular volume status.

Second, excessive intake of hypotonic fluids can dilute serum sodium, a process exemplified in endurance athletes who prioritize hydration over electrolyte replenishment.

Third, certain pharmacologic agents, such as thiazide diuretics, impede sodium reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule, thereby predisposing individuals to dilutional hyponatremia.

Fourth, the central nervous system is exquisitely sensitive to rapid shifts in osmolarity, which explains why cerebral edema manifests as confusion, seizures, or coma in severe cases.

Fifth, clinical guidelines recommend correcting serum sodium at a controlled rate, typically not exceeding 8‑10 mmol/L per 24 hours, to avoid osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Sixth, patient education is paramount; individuals should be taught to recognize early warning signs such as persistent headache, nausea, or gait instability.

Seventh, routine laboratory monitoring-especially after initiating diuretics or changing fluid intake patterns-allows clinicians to intervene before complications ensue.

Eighth, dietary sodium intake should not be drastically reduced without medical supervision, as even modest reductions seldom precipitate hyponatremia absent other risk factors.

Ninth, sports nutrition protocols now often incorporate balanced electrolyte solutions rather than plain water, a practice supported by multiple randomized trials.

Tenth, comorbid conditions like heart failure, liver cirrhosis, or syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) amplify susceptibility and require tailored therapeutic strategies.

Eleventh, the role of vasopressin antagonists has emerged as a targeted approach in specific etiologies, though cost and availability remain considerations.

Twelfth, multidisciplinary care-engaging primary physicians, nephrologists, and dietitians-optimizes outcomes through comprehensive management.

Thirteenth, patient adherence improves when clinicians simplify recommendations, emphasizing thirst-driven fluid intake over rigid schedules.

Fourteenth, emerging research suggests that genetic polymorphisms may influence individual variability in sodium handling, opening avenues for personalized medicine.

Fifteenth, in summary, a nuanced understanding of hyponatremia integrates pathophysiology, prudent fluid and medication management, vigilant monitoring, and patient‑centered education.

Sara Spitzer

Nice breakdown, but the long paragraph could use sub‑headings for readability.

Otherwise solid.

Jennifer Pavlik

Thanks for sharing these tips-very helpful for anyone worried about low sodium.

Stay safe out there!

Jacob Miller

While the optimism is appreciated, many readers might need more concrete action steps.

Consider adding a checklist.

Anshul Gandhi

Everyone’s told to trust mainstream medical advice, but why aren’t they warning about water toxicity more loudly?

There’s hidden data the big pharma doesn’t want us to see.

Stay critical.